Introduction with remarks on digital restoration of the Richmond Caligula and its methodological implications |

Bernard Frischer |

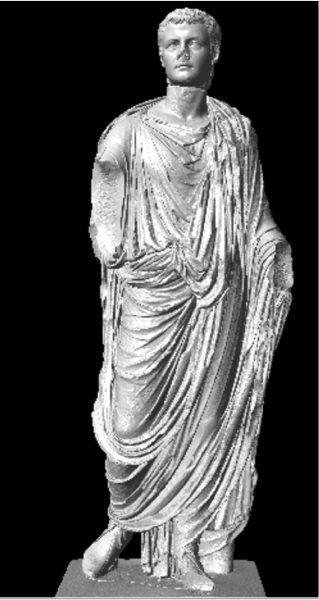

Background. This project, generously supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities (grant # RZ-5221), aimed to increase scholarly and public understanding of one of the most important works of Roman art in an American public collection: the over life-size statue of the Emperor Caligula in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Virginia (The Arthur D. and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 71-20; height: 203.2 cm; figure 2, left).

The goals of the project were to: (1) undertake new interdisciplinary and technical studies of the Richmond Caligula to promote a better understanding of the statue's ancient topographical context, appearance, and cultural significance; (2) present our preliminary findings at a public conference; and (3) make the final results available at no cost over the Internet.

The first goal guided the selection of the research team (figure 1). Mark Abbe and Kathy Gillis collaborated on conservation and restoration issues. Maria Grazia Picozzi was asked to trace the modern history of the statue in the hope - brilliantly realized by Picozzi - that it might be possible to discover its provenience. Paolo Liverani then served as the project's topographer, collaborating with Jan Stubbe Østergaard to study the ancient context of the modern find spot. Eric Varner investigated whether the statue was subject to a "memory sanction" in antiquity, i.e., whether or not its head was intentionally removed. John Pollini and Vasily Rudich dealt more broadly with the image of Caligula transmitted from antiquity, both in art and literature. Steven Fine considered the impact of Caligula and his portrait on his Jewish subjects. Peter Schertz treated the reception of Caligula in the modern period.

The group's collaboration went through three stages: on November 21, 2010 it met for a one-day workshop at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The primary goals of the workshop were to familiarize all members of the team with the statue, to hear the results of Abbe's investigations in September 2010 of the condition of the statue and of its polychromy, to present the digital model of the current state of the statue, and to agree on a plan for digital restoration of the statue. On December 4, 2011 it was reassembled for a one-day symposium where the various preliminary findings of team members were presented to the public. Finally, after the symposium, the draft papers were circulated to all members of the team for cross-referencing in the final versions, which were submitted in the summer and fall of 2012. The papers were then edited by Lauren Kyser (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) and Jack Roebuck (Virtual World Heritage Laboratory; hereafter VWHL).

This article has two parts. In the first section, the focus will be on the digital restoration of the statue that was developed in close consultation with Abbe, whose art-historical and conservation expertise was drawn upon to determine how best to supplement the missing parts of the statue, including the lost polychromy. The results were then presented to the other members of the research team for comment and approval. In the second section, more general observations will be made about digital restoration based on the experience gained in the Caligula project.

1.0 Methods and Procedures. The work proceeded in four phases: scanning of the statue, investigation of the statue's state of preservation including non-invasive studies of the statue's polychromy, digital restoration of the missing and damaged marble fabric of the statue, and development of three hypotheses of digital restoration of the statue's coloration.

|

|

| Fig. 2 Left — Richmond Caligula today. Right — State model of the statue. |

1.1 Phase I: Scanning. The statue was scanned by Peter Kennedy and Greg Chaprnka of Direct Dimensions (Owings Mills, Maryland, USA; http://www.dirdim.com), a company that uses scanning devices to capture high resolution data of complex three-dimensional objects. A FARO 12-ft Platinum Arm with FARO V3 laser line scanner was utilized to make 1318 individual scan passes over the statue that were saved in 15 proprietary scan files for a total of 1.5 GB of raw data. Resolution of the scans was approximately 0.25 mm. A 250 million polygon mesh of the resulting point cloud was created using PolyWorks V11. We refer to this as the "state model" (figure 2, right; on the terminology, see Frischer and Stinson 2007: 51).

1.2 Phase II: Investigation of the statue's state of preservation including study of its polychromy. This aspect of the research is described in detail in Abbe's symposium paper. Photo-induced luminescence imaging revealed traces of madder lake and Egyptian blue in the upper right folds of the tunic. The grains of Egyptian blue were very small, which is suggestive of high-quality workmanship. Madder lake and Egyptian blue yield purple, so we know that the clavus area of the toga was painted with at least a purple stripe (toga praetexta). No traces of pigment were found on the head or elsewhere on the statue.

1.3 Phase III: Restoration of the marble fabric of the statue. As noted by Abbe, the surface of the statue has been damaged in many places. Minor scratches and dents are found all over the torso. Major losses include the tip of the nose; the right upper arm, forearm, and hand; the left forearm and hand; the front part of the left foot; and the bottom of the support on the back. There is a gash around the neck where the head has been reattached, and the position of the head on the neck can be debated. The team agreed that such minor and major damage should be digitally repaired. It was not immediately obvious how the arms and hands should be posed. Discussion of the various types and examples of togate statues in Roman art (see Davies 2010) led to the conclusion that the Richmond Caligula was most similar to the bronze statue of L. Mammius Maximus from Herculaneum (Davies 2010: 66, figure 9; National Archaeological Museum Naples, inv. 5591). The digital restoration team was therefore advised to use photographs of this statue as the source of inspiration.

|

|

| Fig. 3 Left — draft 1 of restoration model with black sandals. Right — draft 1 of restoration model with red sandals. Made by Direct Dimensions, 2011. |

Following written instructions provided by Abbe (Abbe 2011), Jason Page and Eric Hall of Direct Dimensions used the software package Zbrush to make the digital repairs including a first draft of a restoration model showing Caligula wearing the toga praetexta. Two versions were made: in one, Caligula's sandals were painted red; in the other, black (figure 3). The two models were delivered to the VWHL in March, 2011. Matthew Brennan (VWHL) continued close collaboration with Abbe, using Zbrush to produce successive drafts and ultimately the final version of the toga praetexta model (figure 4).

|

| Fig. 4 Final restoration model, toga praetexta variant. Made by Matthew Brennan, Virtual World Heritage Laboratory, 2012. Click here for the interactive model. |

|

| Fig. 5 Final restoration model, toga purpurea variant. Made by Matthew Brennan, Virtual World Heritage Laboratory, 2012. Click here for the interactive model. |

|

| Fig. 6 Final restoration model, toga picta variant. Made by Matthew Brennan, Virtual World Heritage Laboratory, 2012. Click here for the interactive model. |

1.4 Phase IV: Three hypotheses of restoration of the polychromy of the statue. In restoring the polychromy of the statue, the research team decided to take into account evidence of color found on other examples of Caligula's portrait, the most important of which is the life-size head in Copenhagen (see Østergaard 2008: 110). It has traces of color, especially on its left side, and has been used as the basis of the experiment in restoring polychromy on two copies undertaken by team member Østergaard. The results are his reconstructions "A" and "B" (see Østergaard 2008: 112-115). These served as sources of information and inspiration for our digital restoration of the head's coloration. For the torso, the research team decided that the evidence found by Abbe (as reported in Abbe 2011) could support three possible restorations: showing Caligula with toga praetexta (figure 4), toga purpurea (figure 5), and toga picta (figure 6). In the absence of any way to decide which of these three is correct or at least the most probable, the team determined that digital restorations should be made reflecting all three possibilities. As the research progressed in the summer of 2011, the team decided that it was unlikely that Caligula's sandals were red and so variants with this color were dropped.

2.0 Representation of uncertainty in digital restorations. In creating our three digital restorations of the lost coloration of the statue, we were inspired by the statement of team member Østergaard that "such research-based reconstructions do not lay claim to accuracy, neither in the details nor in the technical and artistic quality of the original polychrome work. The aim is twofold: to support scholarly research, and to advance public understanding by presenting a version of the monochrome marble originals that is certainly closer to historical reality" (Østergaard 2008: 113).

In more recent work, Østergaard has been admirably pursuing the collaborative research program announced in his 2008 Getty publication to provide "systematic documentation and research combining archaeology, conservation science, and natural science" (2008: 57). The Copenhagen Polychromy Network, based at Østergaard's museum, is carrying out the mission he envisaged of encouraging polychromy studies by cooperating museums and archaeological sites. An online database has been published (http://www.trackingcolour.com/objects), and studies of individual monuments have been published in Tracking Colour, of which three preliminary reports have already been published (http://www.trackingcolour.com/).

While this work is useful and wholly admirable, it does raise an important methodological issue for digital restoration: the random evidence of ancient polychromy that happens to survive on a statue or other monument must certainly be taken into account in any scientific digital restoration; but although such data are necessary, they are usually not sufficient. That is, there is hardly ever enough information to permit a complete restoration of the artifact's coloration; and what can be detected is sometimes not what was originally seen for the simple reason that the first layer of paint is the likeliest to survive yet the least likely to have been seen by the ancient viewer. For example, just because we find evidence of blue, it does not mean that the area in question appeared blue. Blue was sometimes used as a base for silver or gold foil (Giovanni Verri, personal communication 2011). As in the case of the Richmond Caligula, blue was sometimes combined with pink madder to yield purple. Moreover, painters used preparatory layers: these may have a better chance of surviving than does the top coat. Features such as eyelashes could be indicated by underdrawing, which may detectable today but was not seen in antiquity. Finally, as Abbe notes at the end of his symposium paper, we must always bear in mind that "absence of evidence is not evidence of absence."

So as useful as a large database of secure evidence of polychromy undeniably is, we will probably only rarely find ourselves in a position to make a completely certain or even highly probable digital restoration of ancient polychromy. Rather, we will often have to be satisfied with Østergaard's less ambitious goal of digitally restoring in order "to support scholarly research, and to advance public understanding by presenting a version of the monochrome marble originals that is certainly closer to historical reality" (Østergaard 2008: 113). Of course in so doing, we must always take into account any evidence of ancient pigments that we are able to detect and we cannot under any circumstances contradict the evidence. And when we are working with a statue type, we can cautiously supplement evidence from the copy we are digitally restoring with that from other copies of the same type, as Østergaard 2010 does in his study of the Sciarra Amazon. That said, we must always keep in mind the possibility that as Østergaard's database grows, we may find evidence that not all examples of a statue type were painted in exactly the same way: there may well have been variation in the use of color from copy to copy.

Most scholars who have tried to make a digital 3D representation of a monument from the past have inevitably encountered the problem that even if the monument is well preserved, something has changed over time. Perhaps that "something" concerns only minor, and easily remedied, degradation, such as faded paint. Of course, sometimes a great deal has changed, and a monument, such as the first and second Temple in Jerusalem, may be documented by evidence as tenuous as a passing literary description of dubious reliability (see J. Schwartz 2007). In these and analogous cases, creators of 3D models of cultural heritage objects need to know how they should proceed in a way that reigns in mere fantasy and results in a visualization that can stand the test of professional scrutiny and review. That is, they have to know how to deal with the problem of how best to handle uncertainty.

This is by no means a new problem but is a well-known issue in the field of conservation. Philippot, for example, wrote that "the lacuna, be it in a picture, sculpture or monument of architecture, appears to be an interruption of the continuity of the object's artistic form and its rhythm...the only aim of restoration should be to reduce or eliminate the disturbance caused by lacunae in such a way that the intervention can be unmistakably identified as such (i.e., as a critical interpretation)" (Philipott 1976: 374). Of course, this is easier said than done since the lacuna on a physical object can only be supplemented in one way (for a survey of approaches, see Jokilehto 1999: 213-244). As Philipott indicates, conservation theorists have worked out satisfactory solutions for visually flagging supplements, but in the conservation science literature we find little discussion of how to give a visual cue about the degree of certainty behind a given solution.

The use of models to provide hypotheses of restoration is something familiar to conservators. Thus Philippot 1976 (=Philippot 1996:362) wrote that:

| As stated in the Venice Charter of 1964, anastylosis is the only justified form of archaeological reconstruction, because it is the only one that can reestablish the genuine object. Any other kind of reconstruction that the archaeologist may be able to achieve on the basis of fragments, iconographic documents or descriptions can refer only to a knowledge of the lost object. Such a knowledge cannot be identified with the real object without faking: it should, therefore be materialized in drawings or models, but never in actual reconstruction of the object. |

Here, of course, it is the physical, not digital, model that Philippot is calling for. He leaves it unclear how he would have the model maker deal with uncertainty resulting from the inadequacy of the "fragments, iconographic documents or descriptions" that provide (often only partial) knowledge of the lost object. Østergaard 2008: 112-115 provides a case where two physical models of an archaeological artifact were created in order to deal with uncertainty.

Beyond the field of physical conservation, we find a treatment of the subject of digital representation in Torre Dana Zuk's 2008 Ph.D. dissertation in Computer Science at the University of Calgary. Entitled "Visualizing Uncertainty," Zuk comprehensively surveys how uncertainty has been theorized and represented in fields as diverse as geology, medicine, and archaeology, which he handles in chapter five. One conclusion Zuk reaches across all the disciplines he considers is that uncertainty should be considered either in terms of data or as metadata (Zuk 2008: 225). As data, we express it within the visualization through what he calls visual cues such as non-photorealistic rendering (NPR) that disrupt the otherwise realistic rendering of the data (Zuk 2008: 107-110); as metadata we express it outside the visualization through words.

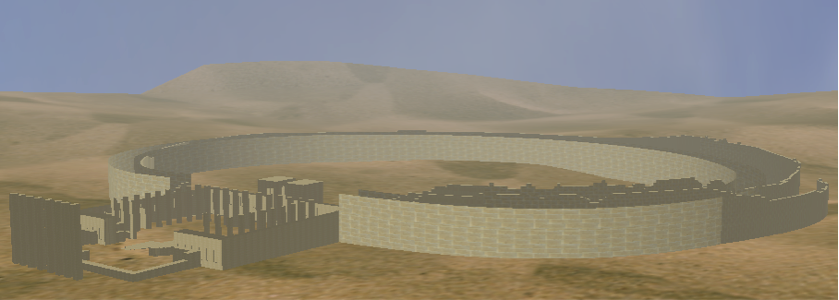

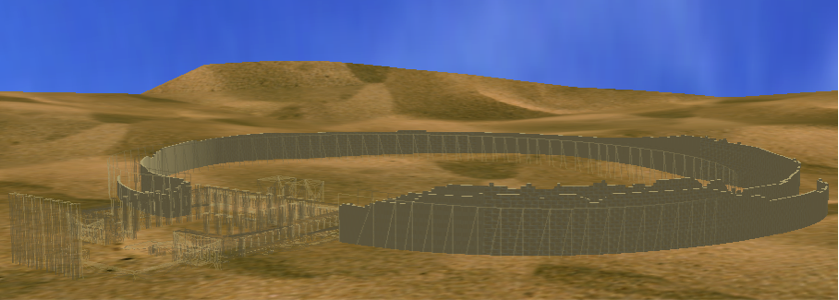

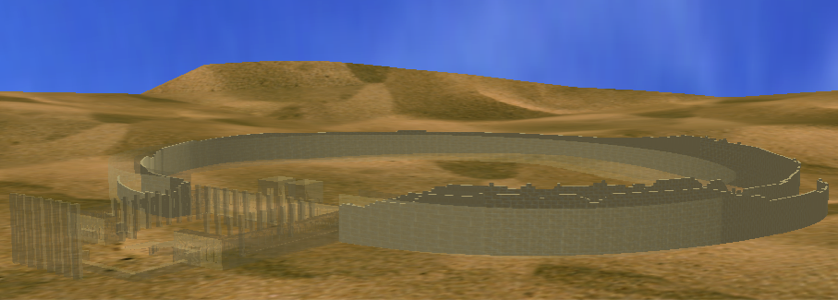

As an example of NPR used as a clue for uncertainty, Zuk uses an example from a site in Marib, Republic of Yemen. The data in the images come from two sources: a theoretical reconstruction of the early building phase on the site based on incomplete data published in Albright 1952 and a second survey in Glanzman 1998. The latter was published after the site had suffered from looting and neglect and only the main oval wall of the sanctuary remained. In figure 7, both data sets are merged, and there are no NPR clues. In figure 8, NPR in the form of wireframe and transparency are used to highlight the hypothetical restoration where there is uncertainty in the data; in figure 9, only transparency is used to flag the uncertainty.

|

| Fig. 7 Digital reconstruction of the site of Marib merging information from Albright 1952 and Glanzman 1998. Source: T. Zuk 2008. |

|

| Fig. 8 Reconstruction of the same site as in figure 7 but with use of wireframe and transparency to give a visual clue about uncertainty. Source: T. Zuk 2008. |

|

| Fig. 6 Figure 9. Reconstruction of the same site as in figure 7 but with use of only transparency to give a visual clue about uncertainty. Source: T. Zuk 2008. |

As can be seen from this example, Zuk's emphasis was on the situation where uncertainty is flagged by the visualization itself. Another approach, not discussed by Zuk, would leave intact the photorealism of the visualization and communicate the nature of the uncertainty through an accompanying text. This is the approach my laboratory took, for example, in our digital reconstruction of the Roman Forum made in the late 1990s and early 2000s where we rendered all the buildings photo realistically but created a related website in 2005 with certainty tables for each monument. For an example, in our treatment of the Curia Iulia (http://dlib.etc.ucla.edu/projects/Forum/reconstructions/CuriaIulia_1/issues) we went systematically through the building from foundations to the roof tiles, listing the evidence that survives and making transparent the elements that had to be hypothetically restored. Each restoration was assigned a level of certainty ranging from low to middle to high. The advantage of this approach over the purely visual methods reported by Zuk is that words can be much more informative and precise than images. Of course, the major disadvantage of our uncertainty table is that many users of our Forum model may not be aware of its existence in a separate part of the website and may naively assume when they look at the visualization that because everything looks photorealistic on the surface, there is no room for questioning the quality of the evidence behind various reconstructions.

In creating our restoration of the Richmond Caligula, we have taken a different approach that represents an attempt to combine the strengths of both the visual and verbal. As has been seen, all three 3D models are photorealistic: there are no NPR visual clues about what we have hypothetically restored. But since we always—whether in a live, public talk such as what presented at the public symposium, on our project webpage, or in a printed scholarly paper— present the three hypotheses together with the state model and photographs of the statue itself, there is an implicit clue transmitted to our viewers that there must be a certain amount of uncertainty about the restoration—otherwise, why would we offer three variants? Another thing we also always mention is Abbe's 2011 report on the condition of the statue, which includes discussion of his three hypotheses of restoration. In short, we have striven to combine the best of both worlds that Zuk kept separate: despite their photorealism, our three models communicate where the uncertainty primarily lies—in the case of the Caligula, in the restoration of the portrait's poorly preserved polychromy—and anyone who wishes can read this report explaining the evidence and analogues used to make the three restoration models. My point is not that we should always avoid the use of NPR to give a visual clue of uncertainty; rather I wish simply to insist that NPR is not the only way that the message about weak or missing evidence can be visually conveyed.

Conclusion. The Caligula project shows the contribution that digital restoration can offer the field of conservation: the possibility of offering alternative hypotheses of restoration so that the refractory paradoxes confronting the restorer of a physical object can be overcome. Much of the debate about whether and how to restore reflects the inescapable fact of the uniqueness of the cultural heritage monument. It can only be repaired to reflect a single hypothesis of restoration, but digital technology easily supports multiple hypotheses. The central tension of traditional restoration grows from the duty to fill lacunae, as set forth by Philippot, and the contradictory ways to do so as articulated by Argan: "(1) 'conservative restoration' (restauro conservativo) giving priority to consolidation of the material of the work of art, and prevention or decay; and (2) 'artistic restoration' (restauro artistico), as a series of operations based on the historical-critical evaluation of the work of art" (Argan 1938, quoted and translated by Jokilehto 1999: 234). With the advent of digital restoration, the physical restoration of the artifact can be based on the approach of restauro conservativo while the digital model can be the vehicle of a complementary restauro artistico. Here we may express the hope that this policy will satisfy those who, like Caroli Federici (Federici 1999 and 2001), deny that digital restoration is truly a form of restoration since it does not operate on the physical artifact. It is certainly true that digital restoration does not replace physical restoration, but once employed it tilts the balance in favor of Argan's conservative restoration of the artifact over artistic restoration, which is no longer necessary.

It is not the least point in favor of such a policy that it was glimpsed, if not explicitly expressed, by Alessandra Melucco Vaccaro in one of her final publications. Warning of the hazards of anastylosis, she wrote, "looking around the world, the tendency toward anastylosis remains unsettling, and it seems not to be regressing even in the age of the virtual image" (2000:213, my translation). She understood that digital restoration has several advantages over anastylosis, not the least of which is the powerful ability to provide any and all hypotheses of restoration that are deemed scientifically possible.

The Caligula project has also shown the usefulness of interdisciplinary collaboration of the kind foreseen by the Collaborative Research Grants program of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Abbe applied conservation science to provide concrete evidence of the statue's original appearance and treatment after the assassination of Caligula. For the first time, the missing parts of the statue could be visualized, including the all-important expressive elements of gesture, pose of the head, and color of the skin and clothing. Picozzi applied archival research to show that the statue's provenience was not, as had been reported, the Theater of Marcellus in Rome but Bovillae. Liverani used topographical methodology to identify the architectural context of the statue at Bovillae, which was probably erected in the Sacrarium Gentis Iuliae. Østergaard, Varner, Pollini, Fine, Rudich and Schertz placed Caligula's portraits (whether in art or literature) into various ancient and modern contexts. Finally, the project resulted in two concrete proposals for follow-up research: removal of the head from the torso in order to perform new tests to determine whether the marble is the same (in which case we can be confident that the head belongs to the statue); and prospection of the site at Bovillae to learn more about the structure located in the nineteenth century.

I conclude with some breaking news. In large part because of our project, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts has recently undertaken new studies of the relationship of the head to the torso. Since the head was found separated from the torso, scholars have always had nagging doubts about whether it truly belongs to the statue. Professor Scott Pike has just sent a letter (included here) to Amy Byrne, a consultant at the museum, reporting that the samples taken of the head and torso are all made of Parian marble from the same block or at least from stones found close together at the quarry. Now that this matter has been definitively settled, we can fairly claim that the NEH-sponsored Caligula Project marks the shift to a new paradigm of interpretation of the Richmond Caligula. And we can express the hope that it will not be long before prospection and, eventually, excavation of the Sacrarium Gentis Iuliae at Bovillae are undertaken so that the architectural context of the statue can be established with comparable authority. At that point, virtual restoration can resume, and we can place the digital models of the statue created through this project into a virtual reconstruction of the ancient architectural setting. The result will be an exemplification of the complementary approaches of "conservative restoration" of the physical fabric of the statue and archaeological site combined with "artistic restoration" by means of what might be called "virtual anastylosis."[1]

Bibliography

Abbe, Mark. "Summary notes on coloring the Richmond Caligula," unpublished report dated March 3, 2011.

Albright, F.P. 1952. "The excavation of the Temple of the Moon at Marib (Yemen)," BASOR 128: 25-39.

Argan, G.C. 1938. "Restauro delle opere d'arte. Progettata istituzione di un Gabinetto Centrale del restauro," Le Arti 1.2: 133-137.

Davies, Glenys, 2010. "Togate statues and petrified orators," in D.H. Berry and A. Erskine, editors, Form and function in Roman oratory (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge) 51-72.

Federici, Carlo. 1999. "Restauro tradizionale e restauro virtuale come 'divergenze parallele,'" Gazette du livre médiéval 34: 49-52.

Federici, Carlo. 2001. "Qualche chiosa al restauro cosiddetto 'virtuale,'" Kermes. La rivista del restauro 43: 9-10.

Frischer, B. and Stinson, P. "The importance of scientific authentication and a formal visual language in virtual models of archaeological sites: The case of the House of Augustus and Villa of the Mysteries," in Interpreting The Past: Heritage, New Technologies & Local Development, The Ename Center, Ghent 11-13 September 2002 International Conference (Brussels, 2007) 49-83. Available online at: www.iath.virginia.edu/%7Ebf3e/revision/pdf/Frischer_Stinson.pdf .

Glanzmann, W.D. 1998. "Digging deeper: The first season of activities of the AFSM on the Maham Bilqñis, Marib," PSAS 28: 89-104.

Jokilehto, Jukka. 1999. A history of architectural conservation (Amsterdam: Elsevier).

Melucco Vaccaro, Alessandra. 2000. Archeologia e restauro (Viella, Milan).

Østergaard, Jan Stubbe. "Emerging colors: Roman sculptural polychromy revived," in The color of life. Polychromy in sculpture from antiquity to the present, edited by Roberta Panzanelli (The J. Paul Getty Museum and the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles) 40-61.

Østergaard, Jan Stubbe. 2010. "The Sciarra Amazon investigation: Some archaeological comments," Tracking Colour, 50-60.Philipott, Paul. 1976. "Historic preservation: philosophy, criteria, guidelines," in Preservation and conservation: Principles and practices, Proceedings of the North American International Regional Conference, Williamsburg, Virginia, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1972 (Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press) 374-382; reprinted in Historical and philosophical issues in the conservation of cultural heritage, edited by Nicholas Stanley Price, M. Kirby Talley Jr., and Alessandra Melucco Vaccaro (The Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, 1996) 358-364.

Schwartz, J. 2007. "Issues in reconstructing a site for which archaeological evidence is lacking: The Second Temple in Jerusalem (Herodian phase)," in Ut Natura Ars, Atti della Giornata di Studi (Bologna, 22 aprile 2002), edited by Antonella Coralini, Daniela Scagliarini Corlaita (University Press Bologna, Imola) 59-70.

Zuk, T.D. 2008. "Visualizing Uncertainty," a thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Computer Science, University of Calgary.

Footnotes

[1]I express my thanks to the Dr. Peter Schertz, Jack and Mary Ann Frable Curator of Ancient Art, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and to Dr. Kathy Gillis, Head of Objects Conservation, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, for permission to scan and study the statue in their museum as part of the Caligula project. Direct Dimensions, Inc. was responsible for 3D data capture, modeling, and digital restoration of the statue. I thank President and Chief Engineer Michael Raphael for his strong support of a project and to Production Manager Peter Kennedy and Engineer Greg Chaprnka for scanning the statue. Special kudos are owed to Industrial Designer Jason Page and Digital Modeler Eric Hall for their painstaking and brilliant work of digital restoration. Matthew Brennan of the Virtual World Heritage Laboratory modified the digital model produced by Direct Dimensions to create the alternative reconstructions necessitated by the overall research project. Heartfelt thanks are also due to the following members of the scholarly team: Steven Fine, Paolo Liverani, Jan Stubbe Østergaard, Maria Grazia Picozzi, John Pollini, Vasily Rudich, and Eric Varner. Without a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (nr. RZ-51221) this project would never have been possible.

Back to Papers

Copyright © 2009-13. Last updated: March 22, 2013.

The Digital Sculpture Project is an activity of the Virtual World Heritage Laboratory.