Reconstructing Epicurus’ Lost Portrait Statue

Bernard Frischer

|

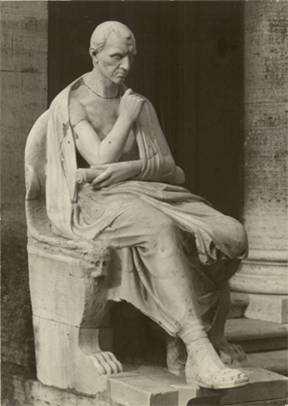

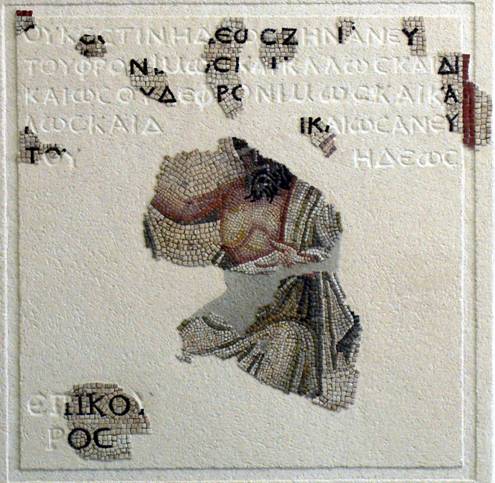

| Figure 1: Autun mosaic from The House of the Greek Authors, Musée Rolin. Photograph: Bernard Frischer.[1] |

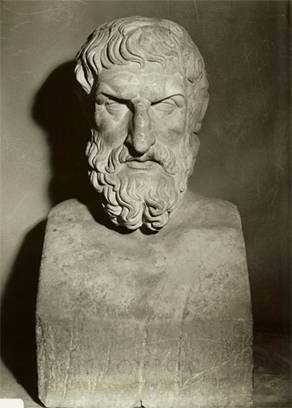

Background. Like many famous Greeks, the philosopher Epicurus (341–270 BCE) was the subject of a full-length sculpted portrait. The original, which probably dates to his lifetime, is lost, but we have many Roman copies in various media and scales. Our only copy depicting the entire statue comes from a mosaic found in 1989–90 in Autun (Augustodunum), France (figure 1).[2] Otherwise, we have seven headless torsos (figure 2) and over thirty torso-less heads (figure 3).[3] The torsos all lack the right arm, giving rise to a debate about how it was to be restored. The mosaic settles the issue: as I had argued before the mosaic was discovered, the arm should be restored pointing forward in a gesture of teaching or greeting. So the reconstruction by Richter, Zanker and others that is based on the right arm bending back toward the head in a “thinker” pose (as is seen, e.g., in the modern restoration in figure 2) is not supported by the evidence.

The mosaic dates to the second century CE and was found in a Roman-era building in the so-called House of the Greek Authors. At least two other authors were depicted on the mosaic: the poet Anacreon and Epicurus' follower, Metodorus. The identifications of all three figures is secured by inscriptions adjacent to the images.

Augustodunum was the capital of the Edui and was known to have prospered during the high empire, a period to which can be dated a theater, amphitheater, and two elite houses on the town's cardo.[4] The House of the Greek Authors was found in April of 1965 in 52, rue de la Grille, when it was partially excavated by G. Vuillemot, a restorer at the Musée Rolin in Autun. This was a limited, emergency excavation, and it resulted in the discovery of a polychrome mosaic with a decorative scheme that was partly geometric and figural.[5] The only figure recognized in 1965 was the head and upper part of the body of Anacreon. On the ground behind the poet were inscribed two quotations from his works (“Bring water, bring wine, boy! Bring me crowns of flowers! Bring them so I can wrestle with Eros!” Anacreon fr. 38 Gentili=fr. 396 Page; and “Let those who want to fight, fight. As for me, let me drink some honeyed wine to the health of my friends, boy!” fragment 49 Gentili=429 Page). On epigraphical grounds, the mosaic could be dated to the late second century A.D. [6] In the nineteenth century, three other mosaics, since destroyed, had been discovered nearby.[7]

In 1985 a small fragment of a text was found in the upper left part of a different panel on the Anacreon mosaic. This time the author could not be identified, but the discovery attested the existence of other figures on the mosaic and gave Philippe Peraldi, the owner of the property adjacent to 52, rue di la Grille, the idea of allowing the archaeological service of the Musée Rolin to undertake further archaeological investigations in his garden. A sondage was undertaken in 1989, resulting in the find of fragments from the same mosaic. They showed the upper part of the figure of an old man. More extensive work continued from July to October, 1990 under the direction of Pascale Picault-Chardron of the city's office of archaeology. After the modern surface was cleaned, remains of the structure were found at a depth of 1.7 meters.

Three building phases were identified. It was determined that the mosaic belonged to the third phase and occupied a room 6.2 meters wide and 10.5 m long. The room had an apse on the south side. The floor of the room (called a “reception room” by the excavator) was raised on suspensurae. Besides the mosaic covering the floor, the walls of the room were richly decorated with marble orthostats, stuccoes, and frescoes of which only sparse remains survive. The mosaic floor was found in an unusual state: no longer attached to the rudus level of the floor, it had been intentionally pulled up and deposited in a scatter of over 200 fragments, covering about 26 square meters. Exactly why and when this was done is not known. The state of preservation of the mosaic thus resembled a puzzle, and its reconstruction has been a great challenge for the restorers.[8]

The first piece of the puzzle to be put back together was the section containing the portrait of Metrodorus, the leading follower of Epicurus. Work on this part of the mosaic, finished in 1992, allowed the restorers to understand the composition of the central part of the design, which is based on a double quincunx with eight panels 76 cm [9] square separated by meander bands in a swastika pattern. Three of the panels survive on the north part of the floor. Anacreon occupied the central panel. The remains of the panel with Metrodorus were found on the northwest part of the room. As in the sculpted portrait (cf. the copy in Copenhagen),[10] it shows the philosopher seated upon a klismos, wearing a himation and wearing sandals. Again, as in the sculpted portrait, in one hand, resting on his lap, he holds a bookroll, while his other hand, turned upward, supports the head. The head is finely made, and, in contrast with the known sculpted representations of an old Metrodorus with a full head of hair, it depicts Metrodorus with a closely cut beard and a high forehead with, apparently, some baldness on top of his pate.[11] One must cautiously write “apparently” since, as the state drawing of the state of the mosaic when it was found shows, the part of the mosaic with the top of the head was, in fact, missing. In the restorer's report, there is general mention of lacunae, but no detailed accounting is given of what these may be and how they were supplemented (if, indeed, any were).[12]

On the ground of the panel is inscribed Sententiae Vaticanae 14 (“We have been born once and there can be no second birth. For all eternity we shall no longer be. But you, although you are not master of tomorrow, are postponing your happiness. We waste away our lives in delaying, and each of us dies without having enjoyed leisure”), signed with Metrodorus' name. The style of the rounded lettering suggests a date sometime in the second half of the second or early part of the third century A.D. This dating is compatible with the archaizing letters of the Anacreon inscription, which also date to the second century A.D. Besides helping to date the mosaic, the inscription is valuable because up to the time of its discovery, Sententiae Vaticanae 14 was attributed by scholars to Epicurus.[13]

In 1993, A. Blanchard was able to identify the third figure hitherto called “an old man.” Noting that the letters found in 1985 came in two sizes (2.5 cm high and 3.5 cm high), and recalling that Metrodorus' name was written in larger letters on his panel than was the quotation, Blanchard was ingeniously able to reconstruct the name of the subject of the “old man” panel as Epicurus.[14] He then could identify the quotation on the panel as Kuriai Doxai 5 (“It is impossible to live pleasantly without living wisely and honorably and justly; and it is impossible to live wisely and honorably and justly without living pleasantly.”).

A line drawing of the Epicurus panel was published in 1993, but the actual restoration of the Epicurus panel took many years. In January 2006 it was reunited with the two other panels in the Musée Rolin. The portrait of Epicurus is fragmentarily preserved showing the aged philosopher seated on a throne with his head, bushily bearded, inclined to the right, wearing a himation. His left arm is bent across his midriff. His right arm is stretched forward and is somewhat bent upward in a gesture of greeting or teaching. As M. Blanchard notes, it is this last feature that makes the Autun Epicurus interesting for scholars of ancient iconography, since it is the only representation of the philosopher that preserves the right arm. And as she notes, the gesture of the arm is practically identical with the one hypothetically reconstructed in the print edition of The Sculpted Word published in 1982.[15]

The representation of Epicurus in the Autun mosaic is our best evidence for reconstructing the lost Hellenistic original. As M. Blanchard-Lemée notes, the Autun mosaic falls into a well-known class of Roman mosaics depicting writers, either alone or in groups. What distinguishes the Autun example is the presence of long quotations since in the other examples known from around the empire quotations either are lacking or are short. Blanchard-Lemée states that the iconography of the mosaic portraits generally derives from sculpture.[16]

Digital reconstructions of the statue. In 2004–5 I undertook a campaign to scan and digitally model in 3D one of the better-preserved busts and torsos attesting Epicurus' lost portrait. Here are the details:

- Statue of Epicurus, Florence Archaeological Museum, inventory 70990. Scan produced by Alessandro Spinetti and Carlo Atzeni, Department of Electronic Engineering, University of Florence.

- Bust of Epicurus, Naples Archaeological Museum, inventory 5465. Scan produced by Tommaso Grasso, Alessandro Spinetti, and Carlo Atzeni, Department of Electronic Engineering, University of Florence.

I conclude by thanking Dottoressa Maria Rosario Borriello, Director of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, and Dottoressa Carlotta Cianferoni, the Director of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze, for permission to scan works in their collections.

Footnotes

[1]

Michèle Blanchard-Lemée, Alain Blanchard, and Pascale Chardron-Picault

graciously sent me their publications on the Autun mosaic. Marga Gervis

helped in many ways to facilitate my access to the mosaic at the Musée

Rolin, and Madame Brigitte Maurice-Chabard generously hosted me at the

museum and gave me permission to photograph and publish the mosaics from

the House of the Greek Authors.

[2]

M. Blanchard-Lemée and A. Blanchard, “Épicure dans une anthologie sur mosaïque a Autun,” Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres Comptes Rendus 1993, 969–984.

[3]

For the sculpted copies, see G.M.A. Richter, Portraits of the Greeks, volume 2 (London: Phaidon, 1965) 195–198; V. Kruse-Berdolt, Kopienkritische Untersuchungen zu den Porträts des Epikur, Metrodor, und Hermarch (Diss. Göttingen 1975); B. Frischer, The Sculpted Word. Epicureanism and Philosophical Recruitment in Ancient Greece (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1982; second, digital edition published in 2006 by The Humanities E-Book Project of the American Council of Learned Societies; URL http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.90022); von den Hoff, R. Philosophenporträts des Früh- und Hochhellenismus (Munich 1994); P. Zanker, The Mask of Socrates. The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity, translated by A. Shapiro (Berkeley, Los Angeles 1995).

[4]

P. Chardron-Picault, Metrodore: un philosophe, une mosaïque. Catalogue for an exhibition at the Musée Rolin, July 6–September 30, 1992 (Autun 1992) 19.

[5]

G. Vuillemot, R. Martin, R. Turcan, “La maison d'Anacréon,”

Mémoires de la Société éduenne 51 (1966) 31–42;

M. Blanchard-Lemée and A. Blanchard, “Épicure dans une anthologie sur mosaïque a Autun,” Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres Comptes Rendus 1993, 969.

[6]

The quotations were published by M. Blanchard and A. Blanchard, “La

mosaïque d'Ancréon à Autun,” Revue des Études anciennes 75 (1973) 268–279.

[7]

P. Chardron-Picault, Metrodore: un philosophe, une mosaïque. Catalogue for an exhibition at the Musée Rolin, July 6–September 30, 1992 (Autun 1992) 19.

[8]

P. Chardron-Picault, Metrodore: un philosophe, une mosaïque. Catalogue for an exhibition at the Musée Rolin, July 6–September 30, 1992 (Autun 1992) 20–27.

Chardron-Picault gives only the width of the room; for the length, see

M. Blanchard in M. Blanchard-Lemée and A. Blanchard, “Épicure dans une anthologie sur mosaïque a Autun,” Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres Comptes Rendus 1993, 983.

[9]

M. Blanchard-Lemée and A. Blanchard give the dimension as 72 cm

(“Épicure dans une anthologie sur mosaïque a Autun,” Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres Comptes Rendus 1993, 971).

[10]

Cf. G. M. A, Richter, Portraits of the Greeks, vol. 2 (London 1965) 202 (Metrodorus, Statue 1; Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek, I.N. 2685).

[11]

P. Chardron-Picault, Metrodore: un philosophe, une mosaïque. Catalogue for an exhibition at the Musée Rolin, July 6–September 30, 1992 (Autun 1992) 33–40.

[12]

Cf. the report by the restorers, Evelyn Chantriaux-Vicard, et al.,

“Conservation – Restauration. Principes techniques et opérations spécifiques sur la mosaïque d'Autun,” in Metrodore, un philosophe, une mosaïque, Musée Rolin 6 Juillet – 30 Septembre 1992 (Autun 1992) 43–46.

[13]

A. Blanchard, Metrodore: un philosophe, une mosaïque. Catalogue for an exhibition at the Musée Rolin, July 6–September 30, 1992 (Autun 1992) 49–54.

[14]

A. Blanchard in M. Blanchard-Lemée and A. Blanchard, “Épicure dans une anthologie sur mosaïque a Autun,” Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres Comptes Rendus 1993, 973.

[15]

M. Blanchard-Lemée in M. Blanchard-Lemée and A. Blanchard, “Épicure dans une anthologie sur mosaïque a Autun,” Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres Comptes Rendus 1993, 976–979.

For reference to The Sculpted Word, see 979n30.

[16]

M. Blanchard-Lemée in Metrodore: un philosophe, une mosaïque. Catalogue for an exhibition at the Musée Rolin, July 6–September 30, 1992 (Autun 1992) 55–57.

Epicurus Model Main Page

Copyright © 2009-13. Last updated: March 22, 2013.

The Digital Sculpture Project is an activity of the Virtual World Heritage Laboratory.